Recalibrating languages: Lostlingual

by Sabira Ståhlberg, polyglot writer and researcher, LangueFlow

In the multilingual poetry collection Lostlingual, Dinara Rasul(eva) recovers her childhood Tatar language, mixing it with her earliest poetic language Russian, and with English and German. The road back to Tatar has been rough: in Qazan, the capital of Tatarstan where she grew up, the Russian imperial narrative, permeating society and taking all kinds of hidden and openly brutal forms for oppressing minorities, induced her to keep her family language strictly for home use only:

When I began to write poems, still in primary school, it was as if I didn’t have the choice of the language in front of me, as Russian had already become the default one. Tatar seemed like it was sealed in a three-litre jar together with cabbage and cumin – it became a language spoken in the kitchen only. (Lostlingual, p. 12.)

Losing a childhood language is to lose part of oneself, one’s family and the worlds they inhabit. This is the individual level of the disappearance of an endangered language on a social level. Losing a minority language means that knowledge and thinking move into majority and mainstream channels, instead of watering the multiple and unique fields one could cultivate with more than one language and culture.

When an author who has written in a majority language turns to a minority language, discarding the rustic stamp and shame attributed to it by the majority and official propaganda, it is not only a deeply personal move but also highly political.

Dinara’s work with the TEL:L workshops and labs, where participants are recovering their lost, stolen and destroyed languages, the anthology Det icke-ryska Ryssland (‘The Non-Russian Russia’) co-edited by her, as well as Травмагочи [Travmagochi] and Lostlingual (both 2025) show that she has broken free from the heavy shackles of the Russian imperial and colonialist ideology.

Rediscovering languages

Lostlingual appears to be all about rediscovering and regaining a lost language, but it contains much more than that. After Russia attacked Ukraine in February 2022, scraps of Tatar language started to come back to Dinara, and she embarked on a journey of remembering. For a linguistically-minded literary scholar, Lostlingual is a treasure trove of code-, script- and other kinds of switching, word and sound play, as well as multilingual graphic design and elements.

Also other words and expressions (called lostlingual words by her) are included: some words in Tatar she misremembered, mixed up or created herself, such as üz-ing. This first lostlingual word (p. 87) is formed of Tatar üz ‘self’ and English suffix –ing. It could be understood, in her own words, as ‘selfing, returning self to oneself’. Some words were connected unintentionally:büre ‘wolf’ in Tatar shape-shifted into a bear (p. 44) due to the closeness between the Tatar and English words.

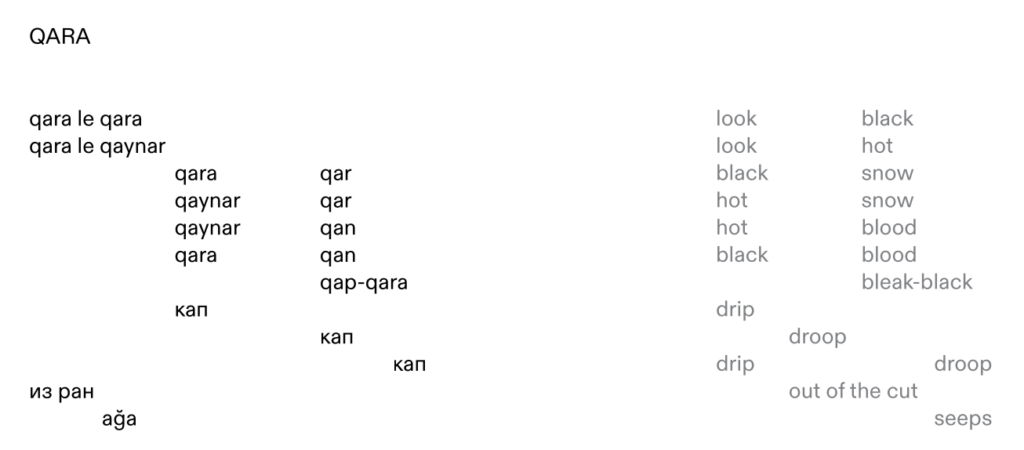

The poems often seem like lyrics for electronic music, and some of them were actually written as songs. Words and expressions are repeated and transformed, gradually or suddenly, leaving the reader standing on the brink of understanding. In order to grasp the meaning, the reader must make a mental leap, but will always waver: what exactly does the author mean?

Beginning of the first poem, Qara. Lostlingual, p. 30

Meanings are far from one-dimensional. This is typical for multilingual writing: hybrids, switching and mixes of various types create a high degree of ambiguity, but also marvel and wonder. Lostlingual, with its distinctive and increasingly varied application of languages and language elements, attests to the fact that it is extraordinary in how many ways languages can be used in creative writing: although Dinara uses similar techniques of repeating, changing words just a little or playing with the same word to create different meanings throughout, the effect is never the same.

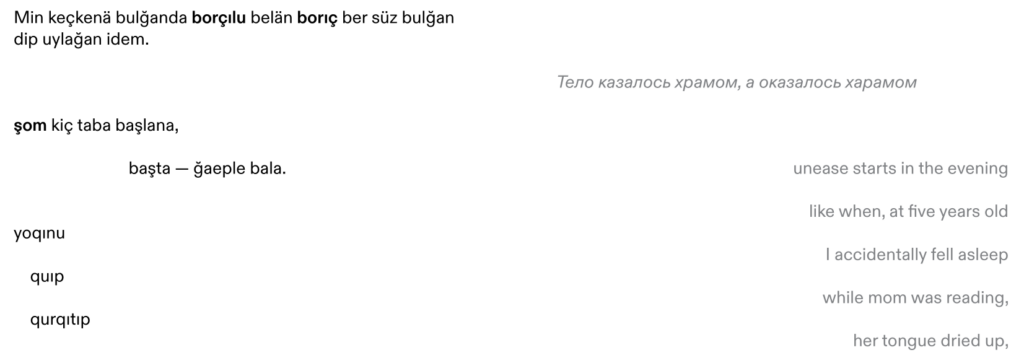

For readers looking for exact self-translations, Lostlingual presents a challenge: poems are only partly translated, many lines and paragraphs have no translation or the translations themselves are multilingual. Looking for exact meanings using web translation platforms will provide only partly sensible translations due to the large number of lostlingualisms, the difference in meanings in the mind of the author and “correct” language, the many hybrid uses of the languages, and the intense word and sound play.

The translations become poems in their own right and should be understood as such. A parallel reading, letting the eye jump from the left to the right page and back again, and moving the eye diagonally over the lines, can yield more meaning and impressions than reading a poem and translation one after the other.

Excerpt from Şom. Lostlingual, p. 88

Recalibrating languages

Lostlingual goes full circle, beginning with the poem Qara and ending with Közge, where the word qara figures frequently. Between these two poems, the author’s Tatar language is fermenting, bubbling and talking like the cabbage in the glass jar, spilling out liquid and growing until it bursts out of the jar. Simultaneously, her Russian, English and German are changing and start appearing in surprising combinations together with Tatar.

A restructuring of thinking and poetic expression is taking place. The author’s attitudes towards the languages are visibly also in a process of revision. What happens is that while the Tatar language is being recovered and repossessed, all other languages and their internal relationships are altered.

From the foreword Why I Write in My Native Language, where Dinara explains in her multilingual English – not striving for correct English but permitting her language to meander and pick up elements and expressions from other languages – to the last poem where Tatar predominates, languages are modified and bent in all kinds of directions.

Excerpt from Qarama qarğa. Lostlingual, p. 64

The reorganised positions and interrelations of the languages emerges clearly in the poems with longer lines, where also the mutual and inter-influences of the languages become more visible than in the shorter “electronic” poems. A de- and reconstruction of all languages is manifested: the languages are not only taken apart and cut into pieces, but they are reassembled in new ways to create fresh and multivocal meanings.

Lostlingual is a book for readers who are ready to enter into new worlds and languages. Tatar is not a generally well-known or studied poetic language in the discipline of literary multilingualism, but it is worth discovering a different world of thinking and expression.

It is also time for literary multilingualism scholars to start paying more attention to authors writing multilingually using less common languages. Lostlingual could be defined as migrant literature due to the biography of the author, but that would be to categorise it too narrowly. This is multilingual literature at its best – curious, exploring, discovering, boundary-crossing, rule-breaking and strongly expressive.

This is not an easy book: there is much pain of loss and of having to confront ideas, values and concepts learnt in childhood, realising that they were all lies created by a machinery whose goal is to destroy you and those similar to you. But there is also a way ahead: this road is multilingual writing for Dinara Rasul(eva) and many others like her, whose languages and voices have been lost or stolen and found again, and it is release, emancipation and liberation.

References

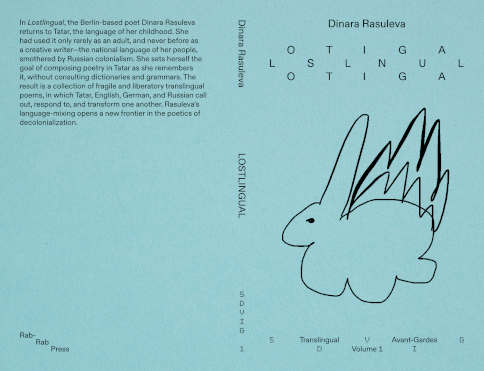

Dinara Rasuleva (2025): Lostlingual. Translingual Avant-Gardes (SDVIG) Series, Volume 1. Editorial note by E. Ostashevsky. Rab-Rab Press, Helsinki.

Динара Расулева (2025): Травмагочи. shell(f).